9. Visualisation And Multi-Modal Interaction

9.1. Introduction

We have previously covered a section on Graphics, which discusses some particular methods of how to draw information on the screen.

However, to deliver an effective and usable system requires a more holistic view that considers the user perspective including what the user is trying to achieve, all the information presented, the methods of interaction, and the complete feedback loop that informs the user as to how the system is responding to their input.

At the Wellcome / EPSRC Centre for Interventional and Surgical Sciences (WEISS) we are bringing together multiple disciplines to ensure that our technology can translate to the clinic effectively.

Prof Ann Blandford, director of the UCL Interaction Centre (UCLIC), now gives an overview of this topic:

9.2. Video

9.3. Notes

(These are the presenter notes from Prof. Ann Blandford, before recording the above video).

9.3.1. Learning objectives

To understand human capabilities in terms of:

Interpreting visualisations and images.

Interacting through multiple modalities.

To understand interactions between people and technology at multiple levels of abstraction:

Perceptual, cognitive, interactive, work.

9.3.2. Levels of Concern: perception, cognition, interaction and work

Making medical images, augmented reality and similar usable by and useful to clinicians requires close collaborations between technology specialists, human factors and Human–Computer Interaction (HCI) specialists, and the intended users of those novel technologies. This should ensure that there is a pipeline from foundational technology leading to usable and useful practical applications in healthcare. HCI input is needed to address the translational challenge at different levels of abstraction:

Cognitive science to understand the cognition and perception behind image interpretation (including in real time): how people focus attention on relevant or less relevant areas of an image, how they identify and interpret areas of relevance, etc.

Human–Computer Interaction to identify user requirements for novel imaging interfaces to support work, and to prototype and test novel interfaces.

Human Factors to understand the broader work system and how that work system needs to adapt to exploit the possibilities offered by new imaging technologies.

9.3.3. Perception and cognition

Norman’s action cycle

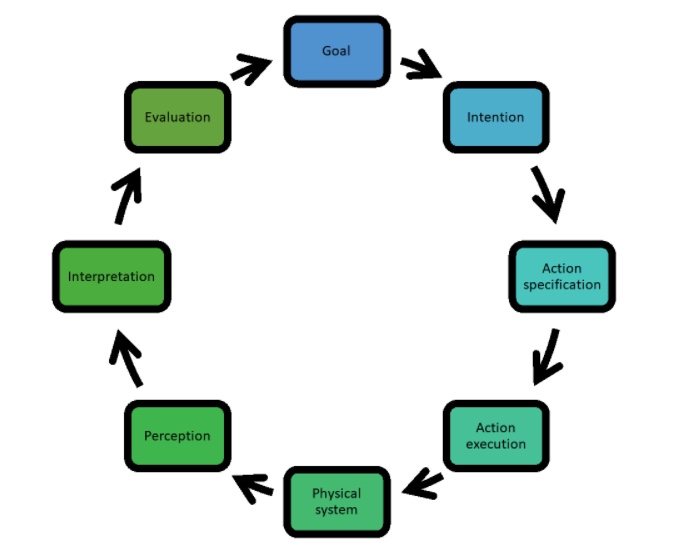

[Norman1988] discusses the way that an individual interacts with technology (such as, but not limited to, a computer system) in terms of an “action cycle”. This is a simplified model of the way in which an individual processes information, forms goals, performs actions and takes in new information to assess whether things are moving in the right direction (so to speak). Although it’s an old model, it’s still a useful way of thinking about people’s interactions with novel technologies. The steps are illustrated in the diagram below:

Someone has a goal. The goal might be at a high level (e.g. remove a tumour) or at a relatively low level (e.g. make an incision, or locate a vein).

In order to achieve that goal, one or more actions need to be performed. In interactive situations, people don’t generally form complete plans, but form partial plans of the things they aim to achieve – i.e., of their intentions. Some intentions are pre-formed; most are responsive to the situation, based on past experience or training.

For each intention, there will be one or more action (again, it depends on the level of abstraction at which these things are described), such as pressing a foot-switch, articulating a command, or moving a mouse and clicking.

Once an action is executed with a system, that system changes state – hopefully in a way that can be perceived (seen, heard, felt, etc.).

What is perceived is then interpreted, in terms of the new system state.

Importantly, that new system state is then evaluated against the goal (did I achieve what I intended? Am I moving closer to my goal? Did I get something wrong?)

In the light of this evaluation, the goal is revised, or a new goal is formed.

Fig. 9.1 Diagram illustrates Norman’s Action Cycle [Norman1988]

Wickens’ resources model considers modalities and codes

[Wickens2008] presents a model – also old now – of how we process information in terms of the different modalities in which information is received, processed and responded to. Based on work in aviation, he focused on visual and auditory information sources (modalities), and information forms (codes) that were spatial or verbal. He argued that for multimodal information to be easily processed, these needed to be coherent with each other. To see examples where information is not coherent, look up the “McGurk effect” or the “Stroop effect”.

According to Wickens’ model, in central processing, the modalities by which information was received is less important than the code (or form) of the information, and the natural responses are manual for controlling spatial information and vocal for managing verbal information.

Obviously, this isn’t completely true, in that I am creating words as I type based on manual input via a keyboard, but it highlights the most natural mapping between information form and interaction technique.

Wickens’ model is clearly simplified; for example, it does not account for some modalities that are central to surgery such as haptic feedback, proprioception, or maybe even smell.

Stimulus-response compatibility

Building on these ideas, a related idea, most commonly applied to physical interfaces, is that of “stimulus-response compatibility”. Stated simply: there should be a natural mapping between the stimulus and the response. Two classic examples from everyday life are that the layout of light switches in a room with multiple switches should map naturally to the layout of the lights being controlled by those switches and that the layout of the controls for a hob should map to the hob layout.

9.3.4. Interaction

Making sense of data / information

We make sense of information in the world (and actively seek it out) through a constant cycle of seeking, finding and interpreting (and using) information. In other contexts such as using a search engine on the Web, this might involve identifying and entering relevant search terms, reviewing search results, following links to read some documents in more detail, and interpreting what you read in the light of what you’re trying to understand [Blandford2010].

In the context of a surgical intervention, this is more likely to involve choosing (probably without thinking about it too hard) where to look, tracking features in an image, and interpreting them in the context of the ongoing activity (e.g.: that’s a vein to be avoided or that’s a polyp to be investigated further or removed), and then acting on that interpretation.

Attentional Resources

The most common metaphor applied when describing how we allocate attentional resources is a “spotlight in the brain”. We focus on some things and ignore others. Visual attention and cognitive attention are often aligned, but not always (think of “daydreaming”).

Attention can also be drawn by external resources such as sounds or lights. The detailed design of these can make important differences to stress and performance, particularly in environments such as an operating theatre.

Focal attention can disrupt situation awareness. It’s a double-edged sword, in that attention is needed for important tasks, but can also lead to “tunnel vision”.

The nature of the work can determine which is more important.

Example: AI in colonoscopy

In a recent study where we compared alternative ways of drawing attention to a suspected polyp in the colon, we found that colonoscopists preferred visualisations that drew attention to the spatial location of the possible polyp, but that made it possible for them to assess that polyp in context and maintain awareness of other features in the colon too.

9.3.5. Designing Interactive Visualisations

When designing interactive visualisations, it is important to consider:

People’s goals – what activity or decision is the visualisation supporting?

What concepts (entities, attributes) matter to them and need to be clearly represented (if possible)?

How people might want to navigate the visualisation (or the system indirectly represented by it).

As a simple example: when my daughter was expecting their first child, she had a 3D scan done. When she showed me it, the first thing she said was “he’s got dimples” – just as she has. The 3D scan enabled us to see features of the unborn child that cannot be accessed from a traditional ultrasound. On the other hand, an ultrasound enables a suitably qualified clinician to answer various questions about the health of the baby that the 3D visualisation does not support.

9.3.6. Understanding work in context

Surgery is a team activity. When designing systems to work in this context, we need to consider:

How work is distributed and how activities are coordinated across the team.

Workflow (tasks) of each individual.

The design of physical space for situation awareness, coordination and focus.

There are various approaches to modelling and understanding the work system, as a step towards designing technology to support work. In this lecture, we’ll briefly consider two: SEIPS and Distributed Cognition. For both of these, data gathering comprises mainly observations and interviews, which will be discussed further in the second lecture. The point of considering the model that is to be developed before you gather data is that it helps to shape what data you gather – i.e., you look out for the kinds of things that you need to include in the model, so it provides a useful focus for data gathering.

SEIPS approach to work system design and analysis

A Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model considers a work system in terms of the elements of the work system (the people, the tasks, the environment, the organisation, and the technologies and tools that are used), the processes that those elements are involved in, and the outcomes, in terms of patient safety; patient care; employee experiences; and the impacts on the organisation.

Distributed Cognition approach

Whereas Norman’s action cycle (discussed earlier) focused on cognitive processing that takes place inside the head, viewing eyes, ears, hands, etc. as input and output channels, the Distributed Cognition approach focuses on how activities are coordinated in the world. In particular, DiCoT (Distributed Cognition for Teams: Berndt et al, ) considers how teams coordinate activity through…

Physical configuration of space, including who can see and hear what.

Design of artefacts that people interact with.

How information flows around the team.

Work processes and coordination.

See [Hazelhurst2007] for an example of the application of Distributed Cognition in surgery.

9.3.7. Summary

In this short lecture, we have taken a quick canter through various theories and models of how people process multimodal information; engage in multimodal interactions with technologies of the kinds typically found in surgery, and particularly image-guided surgery; and coordinate activities in teams such as those typically found in operating theatres.

The theories I have drawn on mostly date back to the previous (20th) century, partly because they have stood the test of time fairly well and partly because more recent theories and approaches add layers of complexity. Drawing on an analogy from physics: Newtonian Mechanics (which has been around for several centuries) helps us to address many every-day problems even though newer theories (General Relativity, etc.) have been developed; we still start with the simpler theories where possible.